Archive for May, 2005

Day 10 – Transatlantic

By Bugs Baer

The wind builds and gets strongest by night. Tomas is sleeping in; he has been repairing the big spinnaker with Ashley all day. We go on deck at midnight UCT, about 10 PM if we were on local time. Question before going on deck: what to wear? Too many warm layers and you sweat a bucket while steering. Too little and you are cold. I pick fleece salopettes (like overalls) under my outer clothes, but no fleece jacket.

Our four-hour watch is at the darkest time. Too late for twilight, too early for dawn, and no moon, if it could get through the clouds, until the last hour. There is too much wind to put up the repaired spinnaker. It is steadily over 30 knots. We are using the blast reacher -- a sail we put aboard for this race, -- and a staysail.

Steering is difficult, but not unusually so. The wind and waves are coming from our starboard quarter -- think about 4:30 on the clock face. At about eight feet high, they are small enough not to be threatening, but big enough to twist the boat's path into a corkscrew. So the helmsman must constantly steer against the corkscrew and respond to puffs and lulls in the wind.

Max Hutter takes the first turn at the wheel, and drives for a little under an hour, He is watching the lighted digital display of speed, course, and apparent wind angle. Someone else calls out changes in wind speed from another display. He is good at holding the course with minimal motion of the helm. Big changes in the angle of the rudder mean that you are dragging a barn door sideways through the water; it is slow. The wind is generally 30 to 35 knots, heavy air but just right to give us speed. We often hit 13 knots, and occasionally 14.

I take over the wheel for a half hour. I need a light on the compass card; my reactions are not tuned to the changing numbers on the lighted digital display. We are running in and out of rain squalls. Pouring now, nothing ten minutes later. As the time goes on, the sweat builds up inside my foul weather jacket; glad I didn't wear the fleece jacket, too. Wind speed is inching up just a bit.

Phil Wilmer takes over next. The wind builds a bit further to top speeds of 37 and 38 knots -- about 44 miles per hour. We adjust and readjust the sails, but basically they are right for the wind. Phil has a knack for getting us surfing down the face of the waves. Several times he goes past the 14's and into the 15's. We chant. ''Fifteen three! Fifteen four! Fifteen five! Fifteen six! Fifteen six! Fifteen five!'' Gradually the exceptional becomes the expected. We are flying.

Christian Jansen's time at the wheel is similar, but the wind is easing just a bit. At one point I find myself saying, ''The wind is slack. Only twenty-nine.'' Then we all start laughing. We now think that twenty-nine knots of wind is slow going.

We keep rotating turns at the wheel. I skip my next turn -- too much wind for comfort. So I cool down and get chilly. Sorry I didn't wear my fleece jacket.

Finally Peter Becker and his 0400 watch appear. It is over; we can sleep.

Â

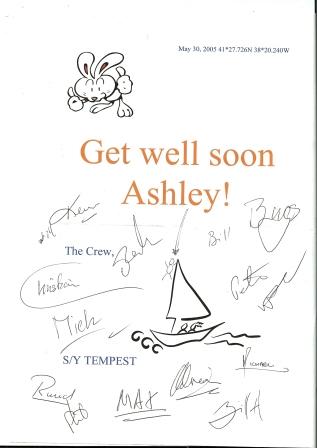

Then another disappointment. The wind goes lighter, The spinnaker Ashley, Tomas and Kevin spent yesterday repairing comes up on deck. Carefully it is hauled up to the top of the mast, tied with its knitting wool strings. The sheet is pulled, the wool ties beak like a zipper opening, the sail spreads -- and rips to pieces again. We take it down and find that, inexplicably, the stronger-than-steel Kevlar reinforcing line along the edges has snapped. Our fastest sail for these conditions is gone again.

When we get the sail out of the water and below decks, Ashley and Kevin have already laid out the repair materials on the saloon table, like an operating room. Next patient, please.

Rolex Transatlantic – Day 9

Tempest had a superb day going until just after midnight UCT, or about 8 PM on the East Coast. We gained distance on every boat in our class, including bigger ones that owe us time. With our big chute flying in up to 26 knots of wind, Tempest roared ahead at twelve and thirteen knots.Around our midnight, as the watches were changing, we started seeing 28 and 30 knots of wind -- time to drop the big chute. We held on and talked about the takedown, then troubles hit twice. The wind pushed the boat into a broach, with the boat heeling over more and rounding up. The boom was pushed into the water, and the preventer -- a line that holds the boom against an uncontrolled jibe -- broke its restraining block. The strain caused a hairline crack in the boom around the vang attachment point. It means damage and strain that we will have to deal with carefully.A few moments later, with a big pop, the wind blew off the top of the spinnaker about ten feet from the top. The bulk of the sail fell into the sea, and had to be dragged out of the water and shoved down the hatch. The top of the spinnaker, still attached to its halyard, wrapped itself around the headstay and remained aloft.

The boat was brought under control and a new sail set, the blast reacher. Tomas went up the mast and retrieved the top of the spinnaker, virtually undamaged by its time in the wind. Tempest returned to very nearly its earlier speed. She lost perhaps a half hour of time, or roughly five miles.

Nobody was injured. Some of the crew have aches and strains from earlier, but everyone is very careful about safety, and good luck lent its helping hand.

Before the midnight messiness, Monday had been a day of learning all around the boat -- Peter Becker taught better steering, Ashley and Tomas taught sewing and sail repair. Will Hubbard, who already knew much, is now an expert splicer. We were smoking.

Steering at these high speeds is tiring. The best and the strongest helmsmen are doing most of it, and they need to rotate often. Despite the surprises and tough work, everyone is pushing his and her hardest.

Ashley is now one handed so requires help in the sewing department so has opened up the “chicken wing†sewing “club†in the salon. Tomas is also a sailmaker so the two of them work through the night on the repair. The repair is not a small one taking 12 hours to repair as the tear went fully across the spinnaker from leech to luff then down the tapes and one of the clews was torn away. The trusty sewing machine is worth its weight.

Ashley is now one handed so requires help in the sewing department so has opened up the “chicken wing†sewing “club†in the salon. Tomas is also a sailmaker so the two of them work through the night on the repair. The repair is not a small one taking 12 hours to repair as the tear went fully across the spinnaker from leech to luff then down the tapes and one of the clews was torn away. The trusty sewing machine is worth its weight.

It is eighteen hours from the start and Tempest is leading its class on

It is eighteen hours from the start and Tempest is leading its class on