Race Reports

Finished and won

by Bugs Baer

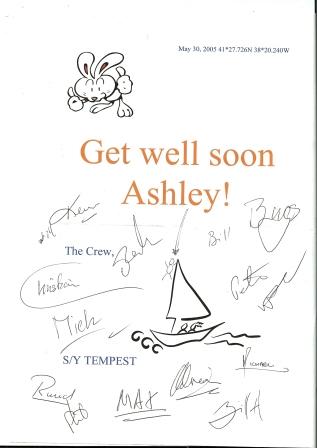

At 1327:00 UTC, Tempest crossed the finish at the Needles, an elapsed time of fourteen days, eighteen hours, and fifty-seven minutes. But it was a tough finish. By 0700 the wind was dying. We carried our lightest spinnaker and moved at less than six knots. By 0800 it was almost dead. The wind shifted around to the east, forcing us to switch to our windward sails and tack toward the finish. It was the first time since the start of the race that we had been hard on the wind. Things began to go wrong. The lightest jib tore on a takedown, and Ashley Perrin and her team set to work pasting on patches. The new jib jammed on the way up. Will Hubbard hitched on his harness and went up the forestay. He found that the forestay tracks for the jibs had broken. Two pieces no longer lined up. Tomas Mark figured out how to twist the grooved pieces to make them line up, and the jib slid into its groove. Slowly we sailed toward the Needles. With ten miles to go, our navigator was asked how long it would take. *Three hours.” As so it was. We were sailing slowly. We were tacking upwind, and the current was soon to turn foul. We were fewer than seven miles from the finish when the wind finally expired. We were making what we thought was the final approach to the finish line when the wind dropped to a whisper. Our GPS told us that we were now being pushed backward faster than we were sailing forward. The tide had turned, and we now had four more hours of foul current to fight. Our navigator, Michael Lawson, pronounced the word of doom: ”Anchor.” It took us ten minutes to sort it out, but at 1225, 4.8 miles from the finish line, we set the anchor and took down our jib. Tempest turned her nose toward the current and hung on the bar-tight line. We found that the light jib had torn again, and again the repair team went to work. On the horizon ahead, we saw the surface of the water darken with ripples. Wind. It is coming toward us. At 1230, no wind. At 1235, no wind. At 1240, a breath of breeze, and we start to set the sail. The patching gang is still frantically sticking strips of sticky back onto the tired old sail. A press boat comes by for glamour shots of the division winner, but instead of glamour, they see a frenzy of repairs. Will Hubbard it up the forestay again. The patchers are sticking tape on sails. The anchor crew is lowering a halyard to pull up the anchor. Five minutes later, the patched sail comes down, and the heavy jib goes up to handle the fresh new breeze. At 1247 were are going again. Now is it just a walk in the woods, an easy sail for the last four miles. We’re getting nearer. Tomas Mark is on the bow calling the finish. Two fingers, one finger, one half finger. We’re over. Our air horn goes off. We shout and scream. We pound each on the on the back and shake every hand. It’s over. We did it. And by a margin of ten hours, we won.

Day 15 – Transatlantic

by Bugs Baer

At 1623:31 UTC (12:23 PM on the East Coast), Tempest passed through the first of the finishing lines at Lizard Point, on the tip of

Land itself was almost invisible, and a foghorn sounded steadily in the grey, misty air as Tempest sped by. For the preceding four hour watch, the boat averaged almost exactly 12 knots in 20 knot air, heeled over under spinnaker, staysail, full main and full mizzen to seize the wind. This is about maximum speed in flat seas.

There are 143 miles left to the final finishing line at the Needles, the western point of the

Almost There

After passing

Everything is focused on the finish and the end of the race. We are jibing downwind for the better wind offshore. We passed

Whisper has lost another twenty miles to us, and Selini is not gaining. The wind will almost die at dawn as a new front arrives from the north. We will beat into the wind for the last few hours. We will have eighteen hours after Selini finishes to hold our handicap, but should finish by noon local time to claim our prize.

We are aware that we are doing everything for the last time. Last dinner. Last look at ''Band of Brothers.'' For my Black Watch, probably midnight will start our last four-hour duty. Then the last dawn, the last miles, and the last of a great adventure.

Day 13 – Transatlantic

By Bugs Baer

Another stuck spinnaker halyard, another trip up the mast, another difficult takedown, another loss of time, another good recovery.

The air went lighter, and by midmorning was in the 19-25 knot range. ''Light'' is relative. Twenty-five knots at home calls for small craft advisories and a hurried race to shelter. But out here it means our speed slowed to the low tens and high nines, so a bigger sail is needed.

We had been flying our heavy asymmetric, a relatively easy sail to manage, but we needed more area and a sail better suited to the almost dead-downwind conditions. This meant a change to the oversize spinnaker -- over four thousand square feet. We pay a handicap penalty of over an hour for having this huge sail aboard, but our navigator says it more than earns its keep in extra speed.

So all non-sleeping hands came on deck, the clew of the sail was spiked, many hands pulled it down -- and it jammed again. Didn't we see this movie yesterday? Up the mast goes Tomas Mark, and finds the same problem. The layer of the halyard has chafed and bunched up again. So the same halyard switch, the same takedown (no crew knockdowns today) the same halyard replacement, and the same puzzle about why it happened.

It takes two hours to be ready, but finally the new sail goes up, and the speed jumps. Although the wind and waves are not particularly difficult, our biggest spinnaker is hard to handle. I happen to be the helmsman, and find it difficult to keep the bow from swinging too far to the right or left.

Everything is fine for a while. I even wave my hands in the air for about five seconds as the boat slides smoothly down the face of a wave, perfectly balanced. My show-off trick is soon punished by the sea gods. I let the bow swing too far to one side, the big sail oscillates to the other, and suddenly we are heeled hard over to the right in a wipeout roundup. Everything above and below decks tumbles to starboard, dishes clatter in their cupboards, and everyone grab handholds to avoid falling. I feel like a pariah. A few hours later, when I am off watch and sleeping in my bunk, two of our best helmsmen consecutively lose control and wipe out. I feel better.

Halyard repairs go on. Tomas has found that there is a small chafe point at the top of the mast that wears out the halyard cover, but not the halyard core. Ashley designs and makes a kind of harness for the top of the mast to hold a halyard away from the chafe point, and Tomas installs it. We hope this solves the problem.

The big spinnaker remains difficult. It begins to wrap itself around the topping lift, one of the horror shows of racing. A huge bulge of fabric in the center of the sail can lose its air if the helming is off. The bulge floats backward and wraps around the headstay or a topping lift. It can wrap over and over, eventually tying itself into a wire-tight knot. It can be untied only over a long time, or by cutting the whole sail down.

The crew is quick to pull the wrap free, before the knot can form. We take the big sail down and go back to the smaller one.

Despite the morning delay in getting the big sail up, noon positions show that we have gained ground substantially on all our competitors. Are we in better wind, or are they more worn and slowed than we are? We haven't stopped pushing for a minute, and perhaps this is paying off.

We are, at midnight, fewer than 400 miles from

We had a good sign, perhaps. We passed another whale today close aboard. He was going his way, and we were going ours, and we didn't bother each other. Perhaps the sea gods have forgiven my hubris.

Day 12 – Transatlantic

by Bugs Baer Tempest is hanging in there, as the boat and the crew — and a surprised whale — all took their bangs in today’s going. Last night’s hydraulic fluid spill cleaned up quickly after daylight. All the sails and lines started the day in working order, but the wind took its toll. Around noon we were reaching with the heavy asymmetric spinnaker in good conditions. Wind speed had been steady for hours at 18 to 23 knots. For hours we had been running under overcast skies with occasional darker patches. No warning. The wind punched us with 33 knots and slammed us over. We rounded up, and the spinnaker lost its wind. Then it filled hard. Everyone rushed on deck to take it down. The blast of wind was easing off. We lined up for a normal takedown, spiked the clew, and the spinnaker flew free to be hauled down, blanketed by the main. Now came the problem. The spinnaker came down about eight feet and stuck. No pulling would get it lower. About six crew were holding the huge sail sheltered behind the main while we tried to analyze the problem. The helmsman let the bow come up into the wind and suddenly the sail filled again, ripping it out of the hands of the gatherers. One of the crew was thrown to the deck hard as a line pulled under his legs rope burning his foul weather gear and leg. The helm came down´and the sail was tamed again. With the boat loafing offwind, Tomas Mark was hauled up the mast to switch the sail to a working halyard and attach a messenger line to the jammed one. It worked. The chute came safely to the deck undamaged, and the old halyard was pulled backward inside the mast. Studying the damaged line, Tomas concluded that the sudden wind had stretched the load-bearing core of the halyard, and the outer dacron sheathing stretched past its breaking point and snapped. Then it bunched up inside the mast instead of sliding smoothly out the halyard block. A smaller sail went up, speed returned, and repairs began on the broken line. Our ship’s doctor, Kevin McMeel, is a veteran of tens of thousands of ocean racing miles, including part of a circumnavigation with Ellen MacArhur. He said, ”I’ve never seen so many torn sails, damaged lines, or personal whacks, burns, and bruises in one race.” This is not Sunday on Long Island Sound. We have read the report of two spinnakers ripping apart and the pole exploding aboard Whisper. Even this bigger, stronger boat could not handle this race unscathed. She is now gaining on us at slightly better than her handicap speed, and is still our closest competition. ”You have to finish to win,” is the race wisdom passed around Tempest. The latest position reports put us still in the lead of our division. Nobody is taking it easy or pulling down the big sails. Whisper will finish about a day ahead of us, and the wind could go light as we slog up the Channel. One of our on-shore routers projects good wind and a finish by midnight Sunday, 72 hours away. Decent speed, but will it be enough? The biggest surprise of the day was a whale in our path. Ruud Blanc spotted a dark shape on the water’s surface, and seconds later Tempest felt a big thump. We had hit a whale, perhaps one sleeping. The boat slowed for a moment. A more direct hit could have brought down our masts. Looking back, Peter Becker saw the shape moving slowly away. We could not judge its size. Nobody aboard, with collectively hundreds of thousands of miles of ocean sailing, had ever hit a whale directly, and we felt badly about this collision. Ruud thought it might have been a humpback whale, but could not be sure. Below decks, the process of living goes on. We are shifting to our warmest clothes, we are at forty-seven degrees north, and air and water are colder. The food remains excellent — cold cuts for lunch, a chicken stew for dinner. The standby watch has been screening ”Band of Brothers’, whose solemn views of struggle somehow seem appropriate to our own challenging voyage. Ashley’s notes: By this point in the trip we were checking the spinnaker halyard every other watch sending someone up the rig to clip on the weather halyard. We they would disconnect the leeward halyard pull it out and inspect for wear and if there was any we had a spare halyard always ready would mouse the damaged one out and put the repaired spare in. Then reconnect the leeward halyard and back on deck we would repair the damaged halyard ready for 6 hours later.

Day 11 – Transatlantic

by Bugs Baer

Tempest passed through a stretch of unexpectedly light wind on Wednesday afternoon, but by night she was back at full speed. During the day, a full-court press by the whole crew fixed her broken sails and brought her computers back to snuff.

Will Hubbard caught the spirit of the operation. "On the upper deck, we have reacher repairs. On the lower deck, we have the spinnaker loft. The doctor is holding sick bay, and Ashley Perrin is taking orders for bags made from Tempest's torn sails." Tomas Mark and his team of staplers and staple-pullers ran the industrial sewing machine on deck. Ashley Perrin and Kevin McMeel cut and glued spinnaker patches below. Then the spinnaker team got its turn on the sewing machine, and during the afternoon the big sail went up again. The spectra luff rope was changed to nylon line which would stretch with the spinnaker cloth and there were no problems with the sail again.

We are treating the spinnakers carefully. We constantly watch the relative wind meter. When the heavy chutes see relative wind over 16 knots, we bring them down. The wind has been cooperative, often coming up to the top speed, then dropping back. We have been seeing 11's and 12's on the speedo all through the night.

Our on-shore weather forecasts have been nearly perfect, but this afternoon we ran into a wind hole. For several hours it was far short of the predicted 25 knots of true wind, and we wallowed along at boatspeed of less than ten knots. You know that somewhere else, your competitors have wind and are moving, and you can't do anything about it.

Our navigator, Michael Lawson, rebuilt the boats computer while the boat rolled, bounced and dripped with moisture. The low point came two days ago when the broach that broke our preventer overturned Michael's coffee mug right into his laptop. Coffee oozed between every key, and the screen went dark. Now he went to work on the laptop -- taking it apart, wiping surfaces dry with paper towels, then using the boat's hair drier to dry the rest. And lo and behold -- it didn't work! All the rest of us would have been stumped. Michael has all the navigation programs, the computer maintenance programs, and the weather programs on his machine. Neither Kevin McMeel's laptop, used for downloading satellite images, nor the boat's computer, used for this email and other boat management programs, can do what Michael's computer can.

So what did Michael do? He went to the fourth computer, the one Ashley had tucked in her sea bag. He loaded all the programs on to hers and we are running again. Our course is now aimed at a narrow band of strong winds between two weather systems, and our information is flowing. I wonder if somewhere, tucked away, there is a fifth computer.

The news comes in that Mari-Cha has passed the first finishing line at The Lizard and has broken the record for this race. The second and final finish will be at the

At midnight our watch went back up for its four-hour hitch. As we barreled along at full speed, Max Hutter, standing near the companionway, noticed a discoloration around his feet. It was oil, spurting from the hydraulic system of the mizzenmast. Another equipment problem to be fixed. What else is new?

Day 10 – Transatlantic

By Bugs Baer

The wind builds and gets strongest by night. Tomas is sleeping in; he has been repairing the big spinnaker with Ashley all day. We go on deck at midnight UCT, about 10 PM if we were on local time. Question before going on deck: what to wear? Too many warm layers and you sweat a bucket while steering. Too little and you are cold. I pick fleece salopettes (like overalls) under my outer clothes, but no fleece jacket.

Our four-hour watch is at the darkest time. Too late for twilight, too early for dawn, and no moon, if it could get through the clouds, until the last hour. There is too much wind to put up the repaired spinnaker. It is steadily over 30 knots. We are using the blast reacher -- a sail we put aboard for this race, -- and a staysail.

Steering is difficult, but not unusually so. The wind and waves are coming from our starboard quarter -- think about 4:30 on the clock face. At about eight feet high, they are small enough not to be threatening, but big enough to twist the boat's path into a corkscrew. So the helmsman must constantly steer against the corkscrew and respond to puffs and lulls in the wind.

Max Hutter takes the first turn at the wheel, and drives for a little under an hour, He is watching the lighted digital display of speed, course, and apparent wind angle. Someone else calls out changes in wind speed from another display. He is good at holding the course with minimal motion of the helm. Big changes in the angle of the rudder mean that you are dragging a barn door sideways through the water; it is slow. The wind is generally 30 to 35 knots, heavy air but just right to give us speed. We often hit 13 knots, and occasionally 14.

I take over the wheel for a half hour. I need a light on the compass card; my reactions are not tuned to the changing numbers on the lighted digital display. We are running in and out of rain squalls. Pouring now, nothing ten minutes later. As the time goes on, the sweat builds up inside my foul weather jacket; glad I didn't wear the fleece jacket, too. Wind speed is inching up just a bit.

Phil Wilmer takes over next. The wind builds a bit further to top speeds of 37 and 38 knots -- about 44 miles per hour. We adjust and readjust the sails, but basically they are right for the wind. Phil has a knack for getting us surfing down the face of the waves. Several times he goes past the 14's and into the 15's. We chant. ''Fifteen three! Fifteen four! Fifteen five! Fifteen six! Fifteen six! Fifteen five!'' Gradually the exceptional becomes the expected. We are flying.

Christian Jansen's time at the wheel is similar, but the wind is easing just a bit. At one point I find myself saying, ''The wind is slack. Only twenty-nine.'' Then we all start laughing. We now think that twenty-nine knots of wind is slow going.

We keep rotating turns at the wheel. I skip my next turn -- too much wind for comfort. So I cool down and get chilly. Sorry I didn't wear my fleece jacket.

Finally Peter Becker and his 0400 watch appear. It is over; we can sleep.

Â

Then another disappointment. The wind goes lighter, The spinnaker Ashley, Tomas and Kevin spent yesterday repairing comes up on deck. Carefully it is hauled up to the top of the mast, tied with its knitting wool strings. The sheet is pulled, the wool ties beak like a zipper opening, the sail spreads -- and rips to pieces again. We take it down and find that, inexplicably, the stronger-than-steel Kevlar reinforcing line along the edges has snapped. Our fastest sail for these conditions is gone again.

When we get the sail out of the water and below decks, Ashley and Kevin have already laid out the repair materials on the saloon table, like an operating room. Next patient, please.

Rolex Transatlantic – Day 9

Tempest had a superb day going until just after midnight UCT, or about 8 PM on the East Coast. We gained distance on every boat in our class, including bigger ones that owe us time. With our big chute flying in up to 26 knots of wind, Tempest roared ahead at twelve and thirteen knots.Around our midnight, as the watches were changing, we started seeing 28 and 30 knots of wind -- time to drop the big chute. We held on and talked about the takedown, then troubles hit twice. The wind pushed the boat into a broach, with the boat heeling over more and rounding up. The boom was pushed into the water, and the preventer -- a line that holds the boom against an uncontrolled jibe -- broke its restraining block. The strain caused a hairline crack in the boom around the vang attachment point. It means damage and strain that we will have to deal with carefully.A few moments later, with a big pop, the wind blew off the top of the spinnaker about ten feet from the top. The bulk of the sail fell into the sea, and had to be dragged out of the water and shoved down the hatch. The top of the spinnaker, still attached to its halyard, wrapped itself around the headstay and remained aloft.

The boat was brought under control and a new sail set, the blast reacher. Tomas went up the mast and retrieved the top of the spinnaker, virtually undamaged by its time in the wind. Tempest returned to very nearly its earlier speed. She lost perhaps a half hour of time, or roughly five miles.

Nobody was injured. Some of the crew have aches and strains from earlier, but everyone is very careful about safety, and good luck lent its helping hand.

Before the midnight messiness, Monday had been a day of learning all around the boat -- Peter Becker taught better steering, Ashley and Tomas taught sewing and sail repair. Will Hubbard, who already knew much, is now an expert splicer. We were smoking.

Steering at these high speeds is tiring. The best and the strongest helmsmen are doing most of it, and they need to rotate often. Despite the surprises and tough work, everyone is pushing his and her hardest.

Ashley is now one handed so requires help in the sewing department so has opened up the “chicken wing†sewing “club†in the salon. Tomas is also a sailmaker so the two of them work through the night on the repair. The repair is not a small one taking 12 hours to repair as the tear went fully across the spinnaker from leech to luff then down the tapes and one of the clews was torn away. The trusty sewing machine is worth its weight.

Ashley is now one handed so requires help in the sewing department so has opened up the “chicken wing†sewing “club†in the salon. Tomas is also a sailmaker so the two of them work through the night on the repair. The repair is not a small one taking 12 hours to repair as the tear went fully across the spinnaker from leech to luff then down the tapes and one of the clews was torn away. The trusty sewing machine is worth its weight.